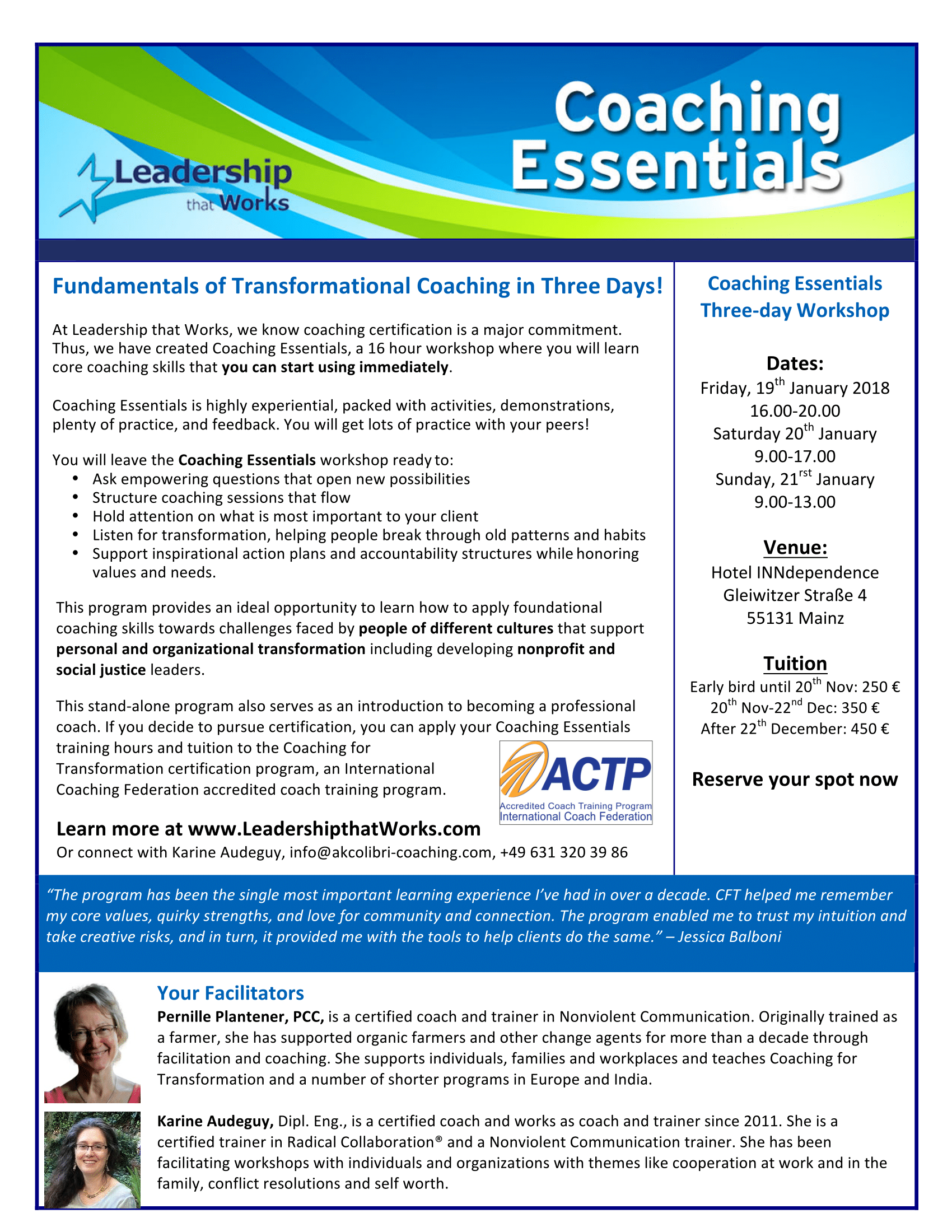

Recommended! On January, 19th-21st 2018, Karine Audeguy (France) and Pernille Plantener (Denmark) offer a Seminar on Transformational Coaching in Mainz, about 20 minutes from Frankfurt Airport. The seminar is suitable for those who want to start a coaching business as well as for those who have already learnt a different coaching techniques and want to widen their spectrum of tools or learn new perspectives helpful in coaching. The methods you learn can be implemented into your consultation or coaching practise right away. Also, there is an option to take this seminar as a beginning for a more extensive training in Transformational Coaching. The seminar will be held in English, but German, French and Danish will also be understood.

For more information, send an e-mail to me or Karine or Pernille! (Their e-mail-adresses are shown in the seminar announcement below).